According to these two articles, one by the Guardian, Peppa Pig pulled: China cracks down on foreign children’s books and one on South China Morning Post, What does China have against Peppa Pig?, the Chinese Government has started to limit the number of picture books originally published overseas in order to both foster local children’s book publication and have a firmer control over the kind of ideology conveyed through the local picture books. (Thanks, Jeff Gottesfeld, for posting these links on Facebook!)

I am monitoring this progress and will report back for those interested in following this topic. But, right out of the bag, I’d like to point out that the number of translated books for children in China has always been huge and overpowering. Look at this screenshot of the top paperback picture book bestsellers on their largest online children’s bookstore: 2 from the Netherland, 4 from the United States, and 2 from France. Not a single title is by Chinese authors or illustrators.

Compare this to the top selling picture books on Amazon in the U.S. (There is no such category, only best selling children’s books.) There are eight picture books in the first twenty titles which are mostly Harry Potter books: First 100 Words by Roger Priddy, The Going-To-Bed Book by Sandra Boynton, The Wonderful Things… by Emily Winfield Martin, Giraffes Can’t Dance by Giles Andreae, The Giving Tree by Shel Silverstein, Oh, The Places You’ll Go! by Dr. Seuss, Richard Scarry’s The Gingerbread Man (Little Golden Book) by Nancy Nolte (Author), Richard Scarry (Illustrator), and Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown. All of them are published in the U.S., by U.S. authors and illustrators. In fact, it has always been rare for foreign, translated work for children to thrive in the U.S. marketplace.

So, I imagine that the need for #OWNVOICE is real and urgent in China.

There is a reason I used this hashtag since I saw that someone invented this other hashtag on Facebook to stress that China Need Diverse Books: #CNDB (modeling after the #WNDB, We Need Diverse Books hashtag) as if the Chinese market is flushed with nothing BUT Chinese creators’ works. The reality is quite the opposite.

Let’s truly examine the full ranges of the issues of picture book fields in these two countries before making judgements regarding the nature and influence of this potential “government mandate.”

The fact is: the U.S. has no government mandate, but a free market, that dictates what gets published and sold. And what we have is usually an extremely U.S. or Western centric slate of titles year in and year out. Any publisher is BRAVE enough to bring a couple of culturally unfamiliar, translated books into the U.S. market is praised, patted on the back, but rarely sees monetary success because of such courageous move. (And why isn’t the Betchelder Award ever cites the Translator along with the Publisher. Or for that matter, why aren’t translators’ names always prominently placed on the cover or title pages? That’s another whole blog post to come.)

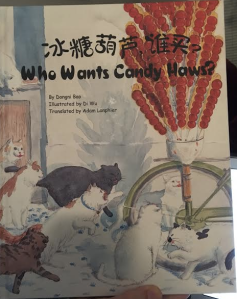

As some of you know already, I am working with Candied Plums, a new children’s book imprint, to bring contemporary Chinese books to the U.S. There is no mandate from anyone or anywhere, except for the publisher’s and my desire to bring more cultural understanding and accessibility to the U.S. readers. These picture books, in my opinion, do not promote the “Chinese/Communist Dogma,” nor do they convey any specific ideology except for displaying all ways that we can be human. These books should be as popular in China as all the imported books. So, perhaps, just perhaps, the publishers who have been working hard at publishing their #OWNVOICES would have a better chance at reaching their #OWNREADERS with this new, drastic mandate from the Government?

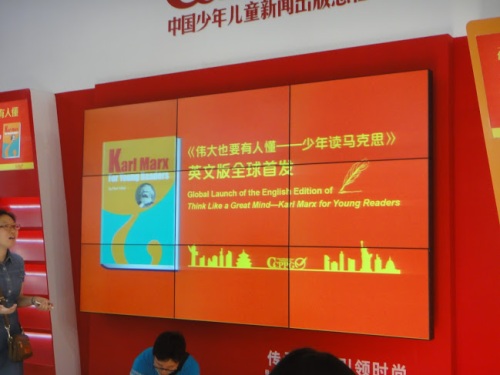

These thoughts went through my mind as I visited Beijing and the International Book Fair with a focus on the local books published for the Chinese young readers.

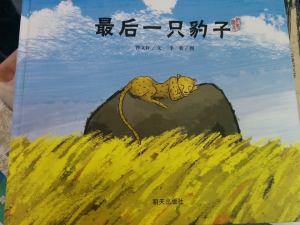

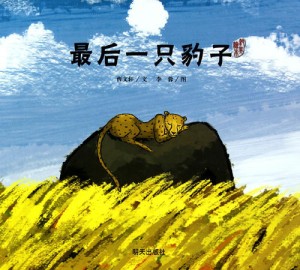

These thoughts went through my mind as I visited Beijing and the International Book Fair with a focus on the local books published for the Chinese young readers. The Last of the Panthers shows the devastating scenario of the “last” of many species and there is no uplifting or hopeful ending when our Panther gives up on itself and falls into the perpetual sleep. It is heart wrenching but so effective. A young person reading the simple text and looking at these gorgeous pictures would acutely feel the pang of loss of such majestic animal and might be inspired to be more responsible in caring for our natural world.

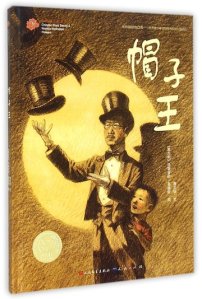

The Last of the Panthers shows the devastating scenario of the “last” of many species and there is no uplifting or hopeful ending when our Panther gives up on itself and falls into the perpetual sleep. It is heart wrenching but so effective. A young person reading the simple text and looking at these gorgeous pictures would acutely feel the pang of loss of such majestic animal and might be inspired to be more responsible in caring for our natural world. Another title is the Hat King. A story set during the Sino-Japanese war when the boy and his grandfather (a magician skilled in “hat tricks”) had to endure the deaths of the boy’s parents at the concentration camp and even when they successfully escaped from the camp, they had no house to go back to any more. And that’s how the tale ends. This is a story almost never told to the children in the U.S. It’s powerful and bleak — but it’s also real and full of familiar affection.

Another title is the Hat King. A story set during the Sino-Japanese war when the boy and his grandfather (a magician skilled in “hat tricks”) had to endure the deaths of the boy’s parents at the concentration camp and even when they successfully escaped from the camp, they had no house to go back to any more. And that’s how the tale ends. This is a story almost never told to the children in the U.S. It’s powerful and bleak — but it’s also real and full of familiar affection.

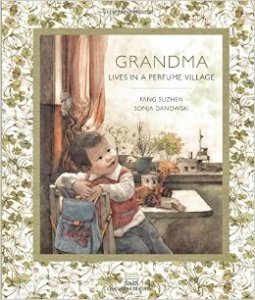

A book recently translated and published by NorthSouth Books by a Chinese author is

A book recently translated and published by NorthSouth Books by a Chinese author is